In the face of a vote of no-confidence, which was expected to be a historic one in Pakistan, Imran Khan decided to plunge the country in a constitutional crisis, by ‘dismissing’ the vote of no-confidence, and by attempting to dissolve the National Assembly under Article 58 (1) of the Constitution of Pakistan.

Before the vote, the besieged PTI tried to employ every trick in the book, and even tried some out of the box thinking: blaming the vote of no-confidence upon a foreign conspiracy, brandishing a piece of paper claiming it to be a letter, claiming the life of the Prime Minister is at risk, attempting to use religion as a political tool. When everything else failed, the PTI government banned the media from the National Assembly and the law minister for a day Fawad Chaudhry moved a motion in the National Assembly, just before the vote of no-confidence, seeking to dismiss the vote on the basis of Article 5 of the Constitution. Article 5 requires loyalty to the state and lays down that obedience to the Constitution and law is an inviolable obligation. It says, and means, nothing more, nothing less.

5. Loyalty to State and obedience to Constitution and law

Article 5 of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973

(1) Loyalty to the State is the basic duty of every citizen.

(2) Obedience to the Constitution and law is the inviolable obligation of every citizen wherever he may be and of every other person for the time being within Pakistan.

However, what the Constitution lay down is that a vote of no confidence, once moved, has to be voted upon by the National Assembly after 3 days and before 7 days of being moved in the National Assembly. The Constitution does not empower the Speaker (or the Deputy Speaker) of the National Assembly to give a ‘ruling’ on the no confidence resolution.

95 Vote of no-confidence against Prime Minister

Article 95 of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973

(1) A resolution for a vote of no-confidence moved by not less than twenty per centum of the total membership of the National Assembly may be passed against the Prime Minister by the National Assembly.

(2) A resolution referred to in clause (1) shall not be voted upon before the expiration of three days, or later than seven days, from the day on which such resolution is moved in the National Assembly.

(3) A resolution referred to in clause (1) shall not be moved in the National Assembly while the National Assembly is considering demands for grants submitted to it in the Annual Budget Statement.

(4) If the resolution referred to in clause (1) is passed by a majority of the total membership of the National Assembly, the Prime Minister shall cease to hold office.

The Deputy Speaker’s action was arguably unconstitutional, and it is likely that the Supreme Court may regard the action as such. The Deputy Speaker has violated the provisions of Article 95 of the Constitution, and in doing so, also violated the provisions of Article 5. Needless to say, in a parliamentary democracy, the Speaker’s role is that of an impartial moderator of parliamentary debate and parliamentary process, and the Speaker (or the Deputy Speaker) ought not to act in a partial or partisan manner.

The Constitution also specifically bars a Prime Minister against whom a resolution of no confidence has been moved from dissolving the National Assembly under Article 58 of the Constitution. Nonetheless, Prime Minister Imran Khan, Information (and Law) Minister Fawad Chaudhry, Deputy Speaker Qasim Khan Suri and President Arif Alvi conspired to dissolve the National Assembly in unconstitutionally.

58. Dissolution of the National Assembly

Article 58 of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973

(1) The President shall dissolve the National Assembly if so advised by the Prime Minister; and the National Assembly shall, unless sooner dissolved, stand dissolved at the expiration of forty-eight hours after the Prime Minister has so advised.

Explanation: Reference in this Article to “Prime Minister” shall not be construed to include reference to a Prime Minister against whom a notice of a resolution for a note of no-confidence has been given in the National Assembly but has not been voted upon or against whom such a resolution has been passed or who is continuing in office after his resignation or after the dissolution of the National Assembly.

(2) Notwithstanding anything contained in clause (2) or Article 48, the President may dissolve the National Assembly in his discretion where, a vote of no-confidence having been passed against the Prime Minister, no other member of the National Assembly commands the confidence of the majority of the members of the National Assembly in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution, as ascertained in a session of the National Assembly summoned for the purpose.

After the Deputy Speaker ‘dismissed’ the no confidence resolution without putting it to a vote, he acting on his own ‘adjourned’ the session of the National Assembly, which under Article 95 of the Constitution is required to vote upon the no confidence resolution.

In the absence of the Deputy Speaker, the opposition ‘put the no confidence resolution’ to a vote, counting 197 votes in favor of the no confidence resolution. If this ‘vote’ is to be considered legal, would mean Imran Khan is no longer the Prime Minister.

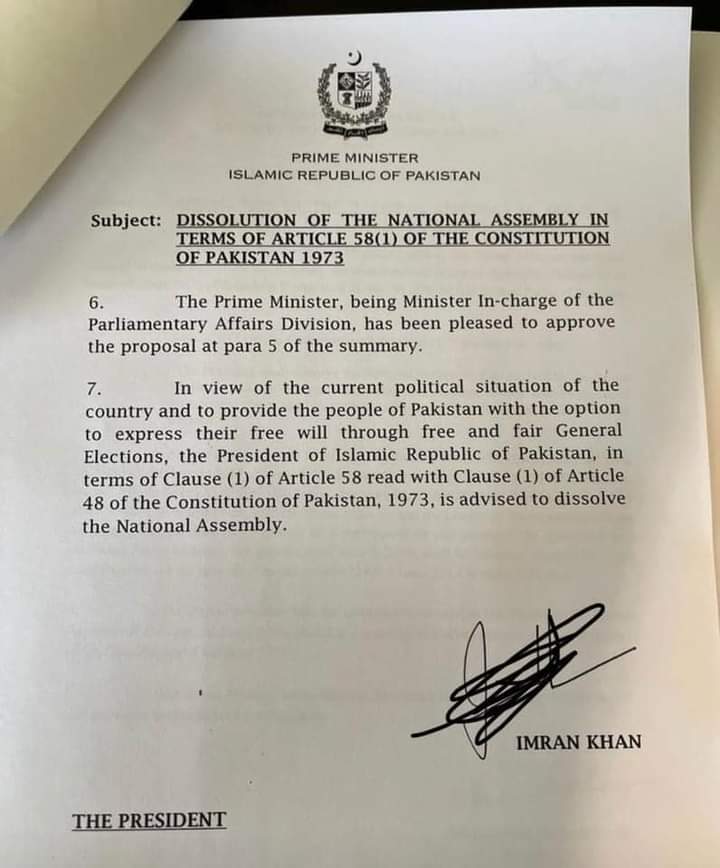

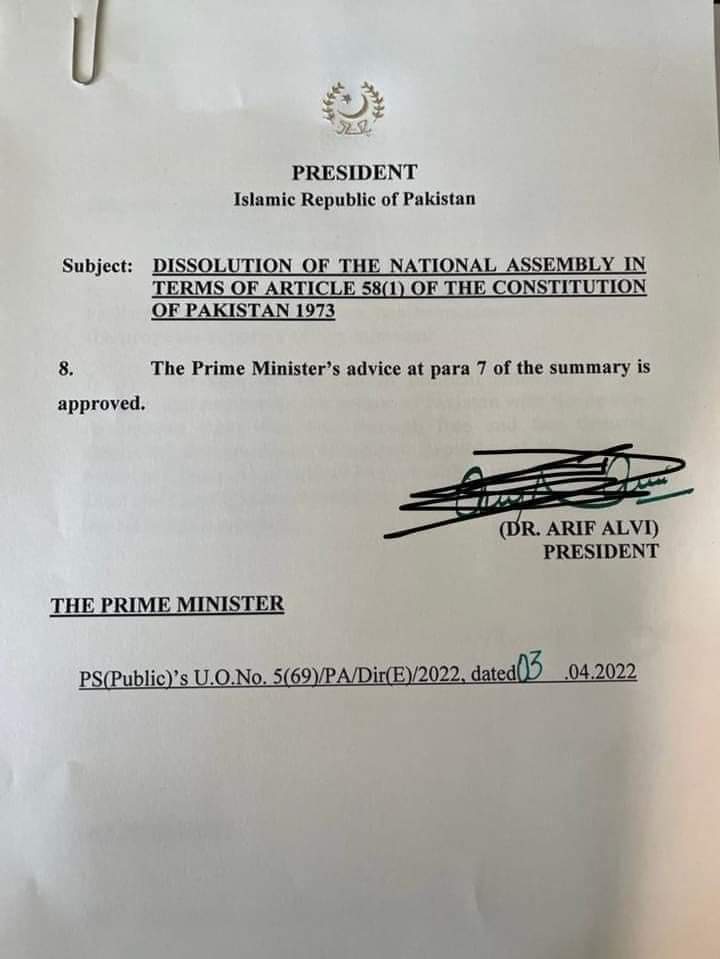

Imran Khan, on the other hand, advised President Arif Alvi to dissolve the National Assembly, which he couldn’t constitutionally do, and upon this advice the President ‘dissolved’ the National Assembly, under Article 58 (1) of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken a suo moto notice of the constitutional crisis which has now been created in Pakistan and a full bench of the Supreme Court heard the matter on a Sunday. While the matter is now sub judice, it is nonetheless safe to say that if the actions of the Deputy Speaker were unconstitutional, the subsequent action of Imran Khan of advising the President to dissolve the National Assembly was unconstitutional as well, and so was the subsequent ‘dissolution’, and thus void ab initio i.e. of no legal effect from the beginning.

What Imran Khan has done is unprecedented in the history of Pakistan: no individual ever, other than the military dictators who form part of our dark history, has attempted to subvert the Constitution the way Imran Khan, Fawad Chaudhry, Qasim Khan Suri and Arif Alvi have done.

In addition to this, Imran Khan had Arif Alvi remove Chaudhry Sarwar from the office of the Governor of Punjab, because, Chaudhry Sarwar claims, he was not okay with what he was being asked to do in Punjab, which he maintains is unlawful and unconstitutional.

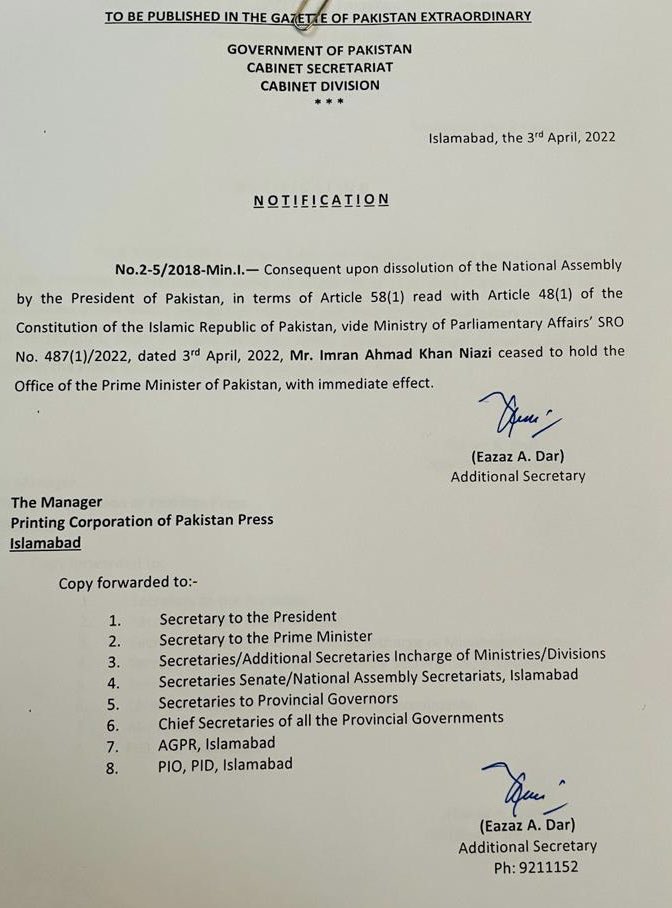

In a shocking turn of events, a notification was issued by the Cabinet Secretariate stating that Imran Khan is no longer the Prime Minister, consequent to the dissolution of the National Assembly.

Fawad Chaudhry claims that the Deputy Speaker’s actions are not amenable to judicial review, citing Article 69 of the Constitution.

69. Courts not to inquire into proceedings of Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament)

Article 69 of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973

(1) The validity of any proceedings in Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) shall not be called in question on the ground of any irregularity of procedure.

(2) No officer or member of Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) in whom powers are vested by or under the Constitution for regulating procedure or the conduct of business, or for maintaining order in Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament), shall be subject to the jurisdiction of any court in respect of the exercise by him of those powers.

(3) In this Article, Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament) has the same meaning as in Article 66.

The judiciary, under the Constitution, is entrusted with the duty to uphold the rule of law and constitutional governance. If a matter is of public importance, or if an action of the Speaker (or the Deputy Speaker) is patently unlawful, the Supreme Court, or a High Court, under their constitutional powers under Article 184(3) and 199 of the Constitution respectively can intervene.

184. Original Jurisdiction of Supreme Court

Article 184 of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973

(1) The Supreme Court shall, to the exclusion of every other court, have original jurisdiction in any dispute between any two or more Governments.

Explanation.- In this clause, “Governments” means the Federal Government and the Provincial Governments.

(2) In the exercise of the jurisdiction conferred on it by clause (1), the Supreme Court shall pronounce declaratory judgments only.

(3) Without prejudice to the provisions of Article 199, the Supreme Court shall, if it considers that a question of public importance with reference to the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights conferred by Chapter I of Part II is involved have the power to make an order of the nature mentioned in the said Article.

199. Jurisdiction of High Court

Article 199 of the Constitution of Pakistan, 1973

(1) Subject to the Constitution, a High Court may, if it is satisfied that no other adequate remedy is provided by law,-

(a) on the application of any aggrieved party, make an order-

(i) directing a person performing, within the territorial jurisdiction of the Court, functions in connection with the affairs of the Federation, a Province or a local authority, to refrain from doing anything he is not permitted by law to do, or to do anything he is required by law to do; or

(ii) declaring that any act done or proceeding taken within the territorial jurisdiction of the Court by a person performing functions in connection with the affairs of the Federation, a Province or a local authority has been done or taken without lawful authority and is of no legal effect; or

(b) on the application of any person, make an order-

(i) directing that a person in custody within the territorial jurisdiction of the Court be brought before it so that the Court may satisfy itself that he is not being held in custody without lawful authority or in an unlawful manner; or

(ii) requiring a person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Court holding or purporting to hold a public office to show under what authority of law he claims to hold that office; or

(c) on the application of any aggrieved person, make an order giving such directions to any person or authority, including any Government exercising any power or performing any function in, or in relation to, any territory within the jurisdiction of that Court as may be appropriate for the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights conferred by Chapter 1 of Part II.

(2) Subject to the Constitution, the right to move a High Court for the enforcement of any of the Fundamental Rights conferred by Chapter 1 of Part II shall not be abridged.

(3) An order shall not be made under clause (1) on application made by or in relation to a person who is a member of the Armed Forces of Pakistan, or who is for the time being subject to any law relating to any of those Forces, in respect of his terms and conditions of service, in respect of any matter arising out of his service, or in respect of any action taken in relation to him as a member of the Armed Forces of Pakistan or as a person subject to such law.

(4) Where- the Court shall not make an interim order unless the prescribed law officer has been given notice of the application and he or any person authorised by him in that behalf has had an opportunity of being heard and the Court, for reasons to be recorded in writing, is satisfied that the interim order-

(a) an application is made to a High Court for an order under paragraph (a) or paragraph (c) of clause (1), and

(b) the making of an interim order would have the effect of prejudicing or interfering with the carrying out of a public work or of otherwise being harmful to public interest or state property or of impeding the assessment or collection of public revenues,

(i) would not have such effect as aforesaid; or

(ii) would have the effect of suspending an order or proceeding which on the face of the record is without jurisdiction.

(4A) An interim order made by a High Court on an application made to it to question the validity or legal effect of any order made, proceeding taken or act done by any authority or person, which has been made, taken or done or purports to have been made, taken or done under any law which is specified in Part I of the First Schedule or relates to, or is connected with, State property or assessment or collection of public revenues shall cease to have effect on the expiration of a period of six months following the day on which it is made:

Provided that the matter shall be finally decided by the High Court within six months from the date on which the interim order in made.

(4B) Every case in which, on an application under clause (1), the High Court has made an interim order shall be disposed of by the High Court on merits within six months from the day on which it is made, unless the High Court is prevented from doing so for sufficient cause to be recorded.

(5) In this Article, unless the context otherwise requires,-

“person” includes any body politic or corporate, any authority of or under the control of the Federal Government or of a Provincial Government, and any Court or tribunal, other than the Supreme Court, a High Court or a Court or tribunal established under a law relating to the Armed Forces of Pakistan;

and “prescribed law officer” means

(a) in relation to an application affecting the Federal Government or an authority of or under the control of the Federal Government, the Attorney-General, and

(b) in any other case, the Advocate-General for the Province in which the application is made.

Rule of Law and supremacy of the Constitution are two fundamental pillars of our system of government. Eroding either of the two is not in the national interest or the interests of any person or political party. Imran Khan’s actions are shameful, dangerous and undoubtedly lowers Pakistan’s stability and credibility and weakens Pakistan’s structure. These actions are undoubtedly unlawful and unconstitutional, and should be condemned by all.

It is pleasing to see the Supreme Court springing into action with the suo moto, as well as the Supreme Court Bar Association which also took the matter to the Supreme Court. It is also commendable that Mr. Raja Khalid Mehmood Khan, the Deputy Attorney General, resigned in protest over these unconstitutional acts.

Leave a Reply